While the wailing and gnashing of teeth that followed the signing of the Finance Bill 2018 into law was going on, another little jab was punched at the banking industry. Our collective national attention was drawn to the brouhaha around the 16% VAT on fuel products and its detrimental effects on the cost of living but tucked away in the Finance Act, was a tiny little section that made changes to Section 31 of the Banking Act. Section 31 generally falls under the part of the Banking Act that relates to information and reporting requirements. The amendment, numbered Section 31A (1), reads, “a bank or financial institution licensed under this Act shall, in respect of all accounts operated at the institution, maintain a register containing particulars of the next of kin of all customers operating such accounts and shall update this register on an annual basis.”

So what was the mischief that the parliamentarians were trying to cure when they had that clause inserted? The Unclaimed Financial Assets (UFA) Act that created the Unclaimed Financial Assets Authority (UFAA) has created a cash rich institution that maintains billions of shillings in unclaimed liquid assets that arise from abandoned bank and SACCO deposits, insurance funds, mobile money funds, listed company shares and unclaimed dividends to name a few. In their fairly transparent and data rich website, the UFAA has published its past financial statements and I pulled up the most recent publication which is for the financial year ending June 2017. As at that date, the Authority held in its own name Kshs 8.5 billion in assets received from banks, Saccos, insurance companies etc. and held in trust listed shares valued at Kshs 16.4 billion following notification from other holders such as listed companies. The shares were being held in trust pending transfer of title to the Authority.

The UFA Act is an easy to read piece of legislation that is duly prescriptive on when a presumption of asset abandonment occurs. In the case of bank accounts, there is a presumption that the owner of the account has “abandoned” the funds if there has been no communication from the account holder in five years. The assumption being made by this amendment is that requiring banks to keep a record of next of kin will trigger an alert to the next of kin about dormant funds lying in a bank account, which might prevent them being swept into UFAA.

Folks, banks are bound by the common law principles of confidentiality as well as statutory requirements relating to non-disclosure of information in the same part of the Banking Act that they are trying to amend. Further north of the newly inserted section lies its cousin Section 31 (2) of the Banking Act which clearly states, inter alia, that “except as provided in this Act, no person shall disclose or publish any information which comes into his possession as a result of the performance of his duties or responsibilities under this Act and, if he does so he shall be deemed to have contravened the provisions of this Act”. The Act later provides exceptions to the rule, which include provision of information to the Central Bank, to credit reference bureaus, to the Kenya Deposit Insurance Corporation , fiscal and tax agencies, fraud investigative agencies and generally any entity whose business it is to have critical information about an account holder. At no point are next of kin (and that word in Kenya is often used quite loosely) envisaged as being of statutory importance for the breach of confidentiality rule to apply.

So here is why there are two fatal flaws in the drafting of the next of kin rule. Firstly, it is virtually impossible to hand over to any Johnny-and Janey-come-lately funds held in a bank account outside the context of a succession framework. The law of succession assumes such funds to be part of the deceased’s estate and can only be distributed within a testate or intestate framework. Secondly, as earlier stated, both common law principles as well as express legislation require banks to maintain confidentiality of their clients, which requirement is presumed, by common law, to extend beyond the death of the client and is therefore not extinguished by their untimely demise.

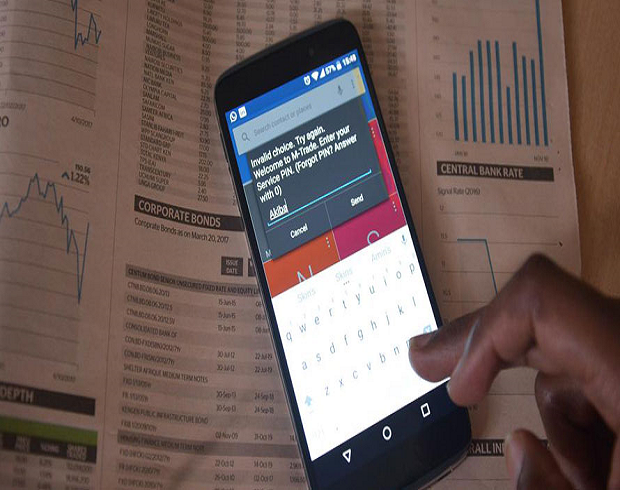

The upshot? You the owner of a bank account in Kenya will now be bombarded by your bank every year from here on to provide details of your next of kin because if you don’t, your bank is liable to pay Kshs 1 million in fines for default for each account. And did you notice that the wording of the law did not differentiate between individual and business customers? Just grin and bear it. As we’ve been conditioned to say in this beloved country: bora uhai!

carol.musyoka@gmail .com

Twitter: @carolmusyoka

carolmusyoka consultancy

carolmusyoka consultancy

@carolmusyoka

@carolmusyoka