Character Development From Farming

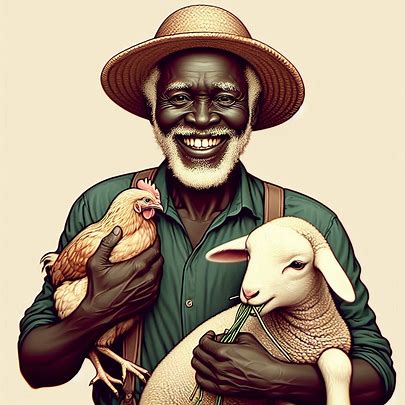

Joram (not his real name), my next-door neighbor at my Laikipia County farm, is the primary source of my miseducation in character development. A retired civil servant, Joram previously spent his days at the local shopping centre doing what some thirsty retirees do. A few months ago, his adult son decided to provide positive choices on where Joram should spend his time by building him an animal pen. Joram Junior, a full time resident of a neighboring county, then purchased 10 goats and 30 chickens to ostensibly keep Senior busy.

What Junior had not factored into his calculations is that the livestock needed steady supply of food. Joram, being of an elderly disposition, has no time to take his new business assets out and about to look for pasture, nor is he inclined to buy poultry feed. So the livestock did what any animal would do under the circumstances. They looked west of the porous fence and found my farm, where my livestock were living in perceived food nirvana. Up until last week, my sheep and goats found themselves knocking heads with the neighbor’s goats as they ate and, on top of that, the chickens would fly into the goat pen and luxuriously pick out the maize kernels from the mixed feed in the troughs. Meanwhile, Joram is innocently playing the “I am both too elderly to be chastised and too tired to look for food for my livestock ” game and a visit to the local chief’s camp to arbitrate this neighborly dispute is in the offing. That’s if I don’t slaughter those confounded chickens first for a month of roast chicken dinners.

I share this story not for the sake of evoking sympathy, but because livestock farming has a number of primary ingredients for success, the largest being food security. If you cannot provide a consistent and safe source of food for your animals all year round, you will shed premium tears. Consequently, commercial livestock farmers vertically integrate by growing feed crops such as sunflower, sorghum, maize silage, napier grass amongst others to provide the required level of nutrients required to successfully increase the yield of animal byproducts such as meat, eggs and milk.

The domestic livestock farmer who keeps a few sheep and goats, one cow for milk and a few hens for eggs may have a different view on long term sustainable animal feeds. He has more things to worry about like eking out a living from the small farm for him and his family. In my farming corner of Laikipia, quite a number of my neighbors are doing large scale commercial farming. The only reason I know this is because when looking for casual laborers, we have to give a crew at least 48 hours’ notice. Demand for casual labor is fairly high, which then impacts the labor pricing, which then impacts the ability of the subsistence farmer to get extra hands on deck to help in planting, weeding and harvesting of their own crops or looking after their animals. With free primary education and a strong local administrative policy of ensuring all children go to school, subsistence farmers also lose out on the previous practices of using free child labor.

My neighbor Joram could do with some help. Someone to shepherd his goats that keep jumping the fence into my farm to eat the pasture for my animals. Someone to find feed for the chickens. Joram Junior didn’t think of that when purchasing the live assets for his retired and very tired father to maintain. An individual’s issue has now become a community problem.

My farm worker shrugged his shoulders when I purported to bring the individuality of my city upbringing into the solution. “Madame hatuwezi chinja hizo kuku,” was his weary response to my suggestions of slaughtering the trespassers. He is right though. It is just not the neighbourly thing to do upcountry, where a sense of community appropriately reigns supreme in the last bastion of African cultural living. Consequently, I have now been forced to finance an unbudgeted-for fence high enough to keep both the chickens and the goats out. Two days ago, one hen escaped, flying high over the new fence to seek the unfettered nourishment that it had become accustomed to. This time, my exasperated worker plucked out the one flying feather that enables the trespasser to get aerial lift. Reports reaching my desk are that the trespassing hen is now grounded on its side of the fence, and likely has advised colleagues about the danger of working that lift feather. Meanwhile, my character development forges shakily ahead.

info@carolmusyoka.com

info@carolmusyoka.com

carolmusyoka consultancy

carolmusyoka consultancy

@carolmusyoka

@carolmusyoka