Elvis has left the IEBC building

Following the dramatic resignation of Commissioner Roselyn Akombe mid last week, the immediate thought that came to mind to summarize the sensational exit was:“Ladies and gentlemen, Elvis has left the building. Thank you and goodnight!”

The phrase “Elvis has left the building” was often announced at the end of Elvis Presley’s concerts to encourage rabid fans to accept that there would be no further encores, and that they should pack up and go home. The phrase has morphed from its American pop culture origins into a generally accepted euphemism for someone’s departure, dramatic or otherwise.

On August 14th 2017, shortly after the elections, I opined in this column that the corporate governance structure of Kenyan constitutional commissions and the Interim Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) in particular, was a unique mongrelization of the executive and oversight roles of a body corporate. The IEBC Act creates a commission made up of 8 members and a chairperson. The Act also creates the role of a secretary to the commission, who shall be the accounting officer of the institution.

A look at the act makes for fairly interesting reading. At no point is the chairman referred to as an executive chairman, nor are the commissioners defined as executive. This executive role can be viewed as being derived from both Article 88 (4) of the Constitution read together with Section 4 of the IEBC Act which states the role of the commission is to oversee the mandate of providing elections and referendums as well as and determining electoral boundaries in Kenya. Section 5(4) of the IEBC Act then gives the executive power to the commissioners when it states that the chairperson and members of the commission shall perform their functions as provided in the Constitution, and the secretariat shall perform the day to day administrative functions. And just for avoidance of doubt, Section 7 (2) of the IEBC Act, states that the commissioners are expected to serve on a full time basis.

Section 10 creates the role of the secretary to the commission who, under subsection (7) (a),shall be the Chief Executive Officer, under subsection (7) (c) shall be the accounting officer and, most importantly, under subsection (7) (e)(i) shall be responsible for executing the decisions of the commission.

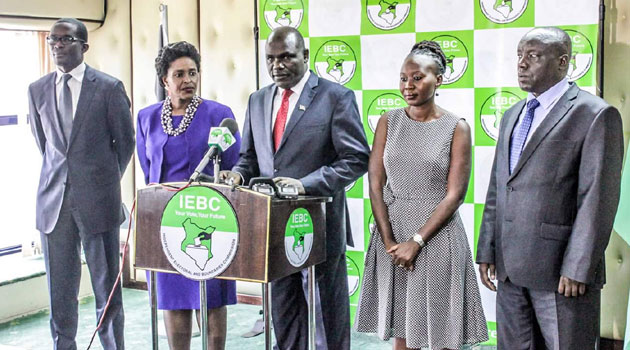

The act thus blesses the CEO with full time commissioners whose decisions he is responsible for executing, while he remains the accounting officer for the financial outcomes of the organization. But the events of last week, following Ms. Akombe’s resignation and the Chairman Chebukati’s stinging indictment of his own commissioners displayed the inherent weaknesses in the mongrel governance structure.

In an ordinary public or private corporate institution, a non-executive board provides oversight and strategic direction to the executive management who undertake the day-to-day operations. By separating the two, it creates a layer of accountability for the executives as well as a point of reference for major decisions that need “independent” eyes to probe the justification and rationale that guided the thinking behind the decision. Equally important, it allows the chief executive a safe landing in the event that external stakeholders question the decision, as the CEO can simply point upwards and say:“the board approved the resolution.” If you need a recent illustration, look no further than the recent case of the Kenya Airways chairman Michael Joseph who vigorously defended the airline’s CEO’s decision to hire five Polish nationals.

However in the case of the IEBC, Chairman Chebukati is, for all intents and purposes, a CEO of an executive team of commissioners who do not have the safety structure of an oversight board to provide strategic guidance and independent thinking that questions those very decisions.

Those decisions must be taken in utmost good faith. Article 250(9) of the Constitution of Kenya states that a member of a commission, or the holder of an independent office, is not liable for anything done in good faith in the performance of a function of office. This is further entrenched in Section 15 of the IEBC Act that provides the same protection from personal liability for commissioners and officers for acts done in good faith. If Ms. Akombe and Mr. Chebukati’s allegations last Wednesday are to be believed, then good faith has also left the building. All the commissioners and the officers of the IEBC must remember that they will be personally liable for any action, claims or demands that may arise in future for decisions taken in bad faith.

Twitter: @carolmusyoka

carolmusyoka consultancy

carolmusyoka consultancy

@carolmusyoka

@carolmusyoka